Saturday, June 29, 2013

Sunday, June 23, 2013

Sobel Wiki: impeachy

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is on Bruce Hogg, the fifteenth Governor-General of the Confederation of North America, and an ardent isolationist.

Being an isolationist was not unusual for a North American politician of Hogg's generation. The backlash against the Starkist Terror of 1899-1901 had made isolationism the bipartisan consensus position in the C.N.A. It was Hogg's main opponent, Douglas Watson of the Liberal Party, who was the outlier in calling for increased military spending and closer ties to Great Britain. So, when North American business mogul Owen Galloway announced his opposition to Watson's military spending bill in July 1934, Hogg was prepared, if you'll pardon the expression, to go hog-wild. He even went so far as to introduce an impeachment measure against Watson in January 1935.

Which was a rather odd thing to do, given the way the C.N.A.'s government was organized. The C.N.A. was basically a parliamentary democracy, with the Governor-General, the head of government, appointed by the majority party in the Grand Council, the legislature. Sobel even specifically says on page 85 that the Governor-General "would serve so long as he retained the confidence of that body." And to prove it, the C.N.A.'s very first Governor-General, Winfield Scott, fell from power after losing a confidence vote in April 1849. So what's with all this "impeachment" stuff? If Hogg wants to stop Watson, all he has to do is introduce a no-confidence vote, and if a majority of the Council disapproves of Watson's foreign policy (and Sobel makes it pretty clear that they do), then Watson is gone, and the Grand Council "goes to the country" as the British say: there's a snap election, and the voters decide which policy they prefer.

The problem here, I think, is that Sobel can't stop thinking like an American. He wants the drama of an impeachment fight, but in the headlong rush to finish the book, he's lost sight of the fact that the C.N.A. doesn't have impeachment fights. Chapter 23, which deals with the Starkist Terror at the turn of the 20th century, suffers from the same problem. Sobel wants Governor-General Ezra Gallivan to bravely battle against the war hysteria that grips the C.N.A. in 1899, but Gallivan spends two years fighting to stay in office before he finally resigns. If Gallivan was as unpopular as Sobel says he was, he should have been gone in a week.

For Want of a Nail was a work of great imagination, but there's no denying that Sobel wasn't always as careful with his world-building as he should have been.

Being an isolationist was not unusual for a North American politician of Hogg's generation. The backlash against the Starkist Terror of 1899-1901 had made isolationism the bipartisan consensus position in the C.N.A. It was Hogg's main opponent, Douglas Watson of the Liberal Party, who was the outlier in calling for increased military spending and closer ties to Great Britain. So, when North American business mogul Owen Galloway announced his opposition to Watson's military spending bill in July 1934, Hogg was prepared, if you'll pardon the expression, to go hog-wild. He even went so far as to introduce an impeachment measure against Watson in January 1935.

Which was a rather odd thing to do, given the way the C.N.A.'s government was organized. The C.N.A. was basically a parliamentary democracy, with the Governor-General, the head of government, appointed by the majority party in the Grand Council, the legislature. Sobel even specifically says on page 85 that the Governor-General "would serve so long as he retained the confidence of that body." And to prove it, the C.N.A.'s very first Governor-General, Winfield Scott, fell from power after losing a confidence vote in April 1849. So what's with all this "impeachment" stuff? If Hogg wants to stop Watson, all he has to do is introduce a no-confidence vote, and if a majority of the Council disapproves of Watson's foreign policy (and Sobel makes it pretty clear that they do), then Watson is gone, and the Grand Council "goes to the country" as the British say: there's a snap election, and the voters decide which policy they prefer.

The problem here, I think, is that Sobel can't stop thinking like an American. He wants the drama of an impeachment fight, but in the headlong rush to finish the book, he's lost sight of the fact that the C.N.A. doesn't have impeachment fights. Chapter 23, which deals with the Starkist Terror at the turn of the 20th century, suffers from the same problem. Sobel wants Governor-General Ezra Gallivan to bravely battle against the war hysteria that grips the C.N.A. in 1899, but Gallivan spends two years fighting to stay in office before he finally resigns. If Gallivan was as unpopular as Sobel says he was, he should have been gone in a week.

For Want of a Nail was a work of great imagination, but there's no denying that Sobel wasn't always as careful with his world-building as he should have been.

Sunday, June 9, 2013

Sobel Wiki: The old switcheroo

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is on Alvin Silva, the last democratically-elected President of the United States of Mexico.

Silva is an example of a phenomenon that we see a fair amount of in For Want of a Nail, where two political parties swap programs over the course of a fairly brief period of time. We've seen that happen in our own history, with the Democrats and the Republicans swapping support for and opposition to civil rights. In our own history, though, the change took a century. In the Sobel Timeline, the C.N.A.'s Liberal Party and People's Coalition swap positions on isolationism and military spending very quickly, between the 1938 and 1953 Grand Council elections. Of course, in the Sobel Timeline, this is the result of the rest of the world being wrecked by a world war that the C.N.A. stays out of. For that matter we are told that even in the 1930s there was a significant faction among the Liberals that opposed their leader's military spending program, so it seems to be the case that this faction became the majority over the course of the Global War, while the isolationist majority in the People's Coalition became a minority there.

In the U.S.M., a similar policy swap took place over the interrelated issues of slavery, isolationism, and business regulation between 1920 and 1932. After the restoration of democracy in the U.S.M. in 1902, two major parties appeared: the Liberty Party, which was revived after being driven underground during the Hermión dictatorship, and the United Mexican Party, which took the place of the pre-Hermión Continentalist Party. The Libertarians were strongly isolationist, opposed to slavery, and sought greater regulation of Kramer Associates, the One Big Zaibatsu that dominated the economy of post-Hermión Mexico. The U.M.P. was only mildly isolationist, was content to allow slavery to remain in existence, and was basically in K.A.'s pocket, though Sobel goes to considerable lengths to deny this.

The Chapultepec Incident of 1916 suddenly brought slavery to the forefront of Mexican politics. Even though there were only 103,000 slaves in a nation of 132 million people, most Mexicans were opposed to freeing them. The Mexican political establishment was paralysed: the institution had become intolerable, but it would be political suicide to try to end it. The impass was finally broken in 1920 with the election of Libertarian candidate Emiliano Calles, an army general who had defeated the French in the Hundred Day War and was consequently the most popular man in Mexico. Calles was able to persuade Douglas Benedict, the head of K.A., to support ending slavery, and Benedict was able to use his financial control of the United Mexican Party to ensure passage of Calles' Manumission Act.

U.M.P. supporters, who tended to oppose manumission, were outraged. It was made clear to them that the U.M.P.'s leaders obeyed K.A. rather than the people who voted for them. Assemblyman Pedro Fuentes, a U.M.P. member who had refused to obey orders from Benedict, took advantage of this public outrage to make himself the leader of the U.M.P., and he was able to ride popular resentment of K.A. to victory in the 1926 presidential election. Fuentes spent his entire term attempting to bring K.A. under control, only to find that its control of Mexican politics made it invincible.

This set the stage for the rise of Alvin Silva. Silva was a Libertarian Senator who had faithfully supported the manumission effort. Along with the rest of the Liberty Party, he had accepted Calles' grand bargain with Kramer Associates: the Libertarians would cease attempting to regulate K.A. in exchange for the company's support for manumission. As a result, Silva was a persistent critic of Fuentes' attack on the company. When Silva was elected President in his turn in 1932, he ended Fuentes' attempts to bring K.A. to heel. Instead, he devoted himself to a new cause: bringing unity to the people of the U.S.M. by pursuing an aggressive foreign policy (and thus abandoning the Liberty Party's traditional isolationism along with its traditional hostility to Kramer Associates).

Silva is an example of a phenomenon that we see a fair amount of in For Want of a Nail, where two political parties swap programs over the course of a fairly brief period of time. We've seen that happen in our own history, with the Democrats and the Republicans swapping support for and opposition to civil rights. In our own history, though, the change took a century. In the Sobel Timeline, the C.N.A.'s Liberal Party and People's Coalition swap positions on isolationism and military spending very quickly, between the 1938 and 1953 Grand Council elections. Of course, in the Sobel Timeline, this is the result of the rest of the world being wrecked by a world war that the C.N.A. stays out of. For that matter we are told that even in the 1930s there was a significant faction among the Liberals that opposed their leader's military spending program, so it seems to be the case that this faction became the majority over the course of the Global War, while the isolationist majority in the People's Coalition became a minority there.

In the U.S.M., a similar policy swap took place over the interrelated issues of slavery, isolationism, and business regulation between 1920 and 1932. After the restoration of democracy in the U.S.M. in 1902, two major parties appeared: the Liberty Party, which was revived after being driven underground during the Hermión dictatorship, and the United Mexican Party, which took the place of the pre-Hermión Continentalist Party. The Libertarians were strongly isolationist, opposed to slavery, and sought greater regulation of Kramer Associates, the One Big Zaibatsu that dominated the economy of post-Hermión Mexico. The U.M.P. was only mildly isolationist, was content to allow slavery to remain in existence, and was basically in K.A.'s pocket, though Sobel goes to considerable lengths to deny this.

The Chapultepec Incident of 1916 suddenly brought slavery to the forefront of Mexican politics. Even though there were only 103,000 slaves in a nation of 132 million people, most Mexicans were opposed to freeing them. The Mexican political establishment was paralysed: the institution had become intolerable, but it would be political suicide to try to end it. The impass was finally broken in 1920 with the election of Libertarian candidate Emiliano Calles, an army general who had defeated the French in the Hundred Day War and was consequently the most popular man in Mexico. Calles was able to persuade Douglas Benedict, the head of K.A., to support ending slavery, and Benedict was able to use his financial control of the United Mexican Party to ensure passage of Calles' Manumission Act.

U.M.P. supporters, who tended to oppose manumission, were outraged. It was made clear to them that the U.M.P.'s leaders obeyed K.A. rather than the people who voted for them. Assemblyman Pedro Fuentes, a U.M.P. member who had refused to obey orders from Benedict, took advantage of this public outrage to make himself the leader of the U.M.P., and he was able to ride popular resentment of K.A. to victory in the 1926 presidential election. Fuentes spent his entire term attempting to bring K.A. under control, only to find that its control of Mexican politics made it invincible.

This set the stage for the rise of Alvin Silva. Silva was a Libertarian Senator who had faithfully supported the manumission effort. Along with the rest of the Liberty Party, he had accepted Calles' grand bargain with Kramer Associates: the Libertarians would cease attempting to regulate K.A. in exchange for the company's support for manumission. As a result, Silva was a persistent critic of Fuentes' attack on the company. When Silva was elected President in his turn in 1932, he ended Fuentes' attempts to bring K.A. to heel. Instead, he devoted himself to a new cause: bringing unity to the people of the U.S.M. by pursuing an aggressive foreign policy (and thus abandoning the Liberty Party's traditional isolationism along with its traditional hostility to Kramer Associates).

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

The internet talks to itself

Monday, May 13, 2013

Sobel Wiki: point of divergence

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is on the Battle of Saratoga, the event that serves as the point of divergence for the Sobel Timeline.

Historically, the Battle of Saratoga was a rather drawn-out affair, lasting from the initial contact between the British and American armies on September 19, 1777 to Burgoyne's final surrender on October 17 (or, in the Sobel Timeline, Burgoyne's final victory on October 25). The question naturally arises, then: when, during that period, did the actual point of divergence take place, and what was it?

Here's Sobel, pp. 30-31: "Burgyone attacked on on September 18, but was forced to retreat before Gates' withering fire. Then the Army of Nations advanced toward Freeman's Farm, and once again was repulsed. Decimated and battered, the Army of Nations regrouped to hear Burgoyne's plan. Caution would have dictated retreat into the woods, but he held fast.

"Awakening on the morning of October 8, Burgoyne learned his force was all but surrounded, and would have to fight its way out of a cordon of rebels. Still morale held. As one survivor later wrote, 'The men were willing and ready to face any danger, when led by officers whom they loved and respected and who shared with them in every toil and hardship.'

"Rallying his men, Burgoyne took them to Schuyler's Farm, and the next morning crossed the Fishkill River. Had Gates attacked then, he could have destroyed the Army of Nations. But he hesitated at that crucial moment, spending his time arguing with Arnold, regrouping his forces, and considering his next move. Meanwhile, unknown to the rebels, Clinton's force moved swiftly up the Hudson, and prepared to attack Gates from the rear. Time was working for the British. Burgoyne knew this; Gates did not.

"On October 13, Burgoyne sent a delegation to ask Gates his terms for a truce. The answer was 'unconditional surrender.' Burgoyne replied that he was not unwilling to admit defeat, but insisted his men be allowed to march from the field with all honors. Gates wavered; he wanted the satisfaction of receiving Burgoyne's sword on the field of battle. At the time Gates had ambitions to succeed Washington, who was in bad grace in Philadelphia. Such a victory, conceded on the field, would assure him of supreme command.

"As Gates hesitated, Clinton's force smashed Israel Putnam's rebel army and continued toward Saratoga. Putnam sent messengers with news of his defeat to Gates, but the men were lost in the woods, and never appeared at headquarters. By the time Gates learned of Clinton's imminent appearance, it was too late to do much about it. The rebel general was now obliged to act in an impromptu fashion. His plan was simple. The rebels would attack Burgoyne's position in force, massacring all, and then turn to face Clinton's army, which was expected in a matter of hours.

"The attack came on the morning of October 21. Wave upon wave of rebels advanced on the weakened Army of Nations, and each time they were repulsed. Then, on October 22, Clinton's men broke through Gates' rear."

Historically, after the battle of Freeman's Farm on September 19, Burgyone was considering making another attack on the Americans. However, he received word of Clinton's planned advance up the Hudson to Albany, and chose to sit tight and wait until word reached him that Clinton was near. When he wrote Burgoyne on September 12, Clinton had anticipated launching his attack in ten days. However, it was not until October 3, three weeks after sending his message, that Clinton began his move up the Hudson. Clinton was able to force Putnam to withdraw due to a well-conducted feint, then took Forts Montgomery and Clinton on October 6, leaving the way clear to continue north up the Hudson. Clinton then fell ill, and returned to New York City, leaving General John Vaughan in charge. Clinton ordered Vaughan to "proceed up Hudson's river, to feel for General Burgoyne, to assist his operations", but Vaughan was delayed, and didn't set out until October 15. On October 17, Clinton received orders from General Howe to send 3000 men to support the occupation of Philadelphia, and Clinton ordered Vaughan to turn back.

Meanwhile, at Saratoga, Burgoyne learned that Clinton had been delayed, and on October 3 he put his army on short rations. The next day, Burgoyne called a war council, but it was not until the 5th that he decided to attack the Americans on October 7th. The attack, known as the Battle of Bemis Heights, went badly for the British almost from the beginning, and by the time night fell the British lines had been breached and Burgyone had lost nearly 900 men.

The next day, Burgoyne began to retreat north across the Fishkill River, completing the crossing on October 10. On the 11th, he attempted to lure the Americans into a trap by sending a double agent to tell Gates that he was retreating up the river. The plan failed when a deserter from Burgoyne's army warned the Americans about the trap. On the 12th, Burgoyne and his officers agreed that they had no choice except to surrender, and on the 13th an officer came to Gates to request terms. Gates initially insisted on unconditional surrender, but soon reconsidered. Surrender terms were agreed on the 16th, and Burgoyne surrendered to Gates the following day.

Comparing Sobel with actual history, it seems as though the actual point of divergence must be Clinton setting out from New York City on schedule on September 22. Burgoyne continues to act as he did in our history, retreating north across the Fishkill River on October 9. Sobel doesn't mention the Battle of Bemis Heights, which might mean that it never took place. However, based on Burgoyne's retreat across the Fishkill, it seems likely that it did take place and Sobel simply chose not to mention it. By the time Burgoyne is offering to negotiate his surrender to Gates on October 13, as he did in our history, Clinton is closing in on Albany, and "smashes" an American army under Israel Putnam. Burgoyne by this time has received word of Clinton's approach, and instead of surrendering, he continues to sit tight. When Gates attacks on October 21, Burgoyne is able to drive him off, then attack in his turn the next day after Clinton attacks Gates from behind:

"Heartened by the sound of their comrades' bullets, Burgoyne's ragged force, now numbering less than 2,000, staged its final assault, in this way placing the now-panicky rebels in the jaws of a pincer movement. It was now Gates' turn to flee, and so he did. Within two days the rebels were on the outskirts of Albany, vulnerable to attack, unable to respond. On the afternoon of October 25, Burgoyne offered Gates a generous peace. All his troops could return to their homes, while Gates himself would be free to leave, upon his pledge never to fight again. The proposal was accepted; Gates had no choice but to do so. So ended one of the most glorious episodes in the history of eighteenth century warfare."

Historically, the Battle of Saratoga was a rather drawn-out affair, lasting from the initial contact between the British and American armies on September 19, 1777 to Burgoyne's final surrender on October 17 (or, in the Sobel Timeline, Burgoyne's final victory on October 25). The question naturally arises, then: when, during that period, did the actual point of divergence take place, and what was it?

Here's Sobel, pp. 30-31: "Burgyone attacked on on September 18, but was forced to retreat before Gates' withering fire. Then the Army of Nations advanced toward Freeman's Farm, and once again was repulsed. Decimated and battered, the Army of Nations regrouped to hear Burgoyne's plan. Caution would have dictated retreat into the woods, but he held fast.

"Awakening on the morning of October 8, Burgoyne learned his force was all but surrounded, and would have to fight its way out of a cordon of rebels. Still morale held. As one survivor later wrote, 'The men were willing and ready to face any danger, when led by officers whom they loved and respected and who shared with them in every toil and hardship.'

"Rallying his men, Burgoyne took them to Schuyler's Farm, and the next morning crossed the Fishkill River. Had Gates attacked then, he could have destroyed the Army of Nations. But he hesitated at that crucial moment, spending his time arguing with Arnold, regrouping his forces, and considering his next move. Meanwhile, unknown to the rebels, Clinton's force moved swiftly up the Hudson, and prepared to attack Gates from the rear. Time was working for the British. Burgoyne knew this; Gates did not.

"On October 13, Burgoyne sent a delegation to ask Gates his terms for a truce. The answer was 'unconditional surrender.' Burgoyne replied that he was not unwilling to admit defeat, but insisted his men be allowed to march from the field with all honors. Gates wavered; he wanted the satisfaction of receiving Burgoyne's sword on the field of battle. At the time Gates had ambitions to succeed Washington, who was in bad grace in Philadelphia. Such a victory, conceded on the field, would assure him of supreme command.

"As Gates hesitated, Clinton's force smashed Israel Putnam's rebel army and continued toward Saratoga. Putnam sent messengers with news of his defeat to Gates, but the men were lost in the woods, and never appeared at headquarters. By the time Gates learned of Clinton's imminent appearance, it was too late to do much about it. The rebel general was now obliged to act in an impromptu fashion. His plan was simple. The rebels would attack Burgoyne's position in force, massacring all, and then turn to face Clinton's army, which was expected in a matter of hours.

"The attack came on the morning of October 21. Wave upon wave of rebels advanced on the weakened Army of Nations, and each time they were repulsed. Then, on October 22, Clinton's men broke through Gates' rear."

Historically, after the battle of Freeman's Farm on September 19, Burgyone was considering making another attack on the Americans. However, he received word of Clinton's planned advance up the Hudson to Albany, and chose to sit tight and wait until word reached him that Clinton was near. When he wrote Burgoyne on September 12, Clinton had anticipated launching his attack in ten days. However, it was not until October 3, three weeks after sending his message, that Clinton began his move up the Hudson. Clinton was able to force Putnam to withdraw due to a well-conducted feint, then took Forts Montgomery and Clinton on October 6, leaving the way clear to continue north up the Hudson. Clinton then fell ill, and returned to New York City, leaving General John Vaughan in charge. Clinton ordered Vaughan to "proceed up Hudson's river, to feel for General Burgoyne, to assist his operations", but Vaughan was delayed, and didn't set out until October 15. On October 17, Clinton received orders from General Howe to send 3000 men to support the occupation of Philadelphia, and Clinton ordered Vaughan to turn back.

Meanwhile, at Saratoga, Burgoyne learned that Clinton had been delayed, and on October 3 he put his army on short rations. The next day, Burgoyne called a war council, but it was not until the 5th that he decided to attack the Americans on October 7th. The attack, known as the Battle of Bemis Heights, went badly for the British almost from the beginning, and by the time night fell the British lines had been breached and Burgyone had lost nearly 900 men.

The next day, Burgoyne began to retreat north across the Fishkill River, completing the crossing on October 10. On the 11th, he attempted to lure the Americans into a trap by sending a double agent to tell Gates that he was retreating up the river. The plan failed when a deserter from Burgoyne's army warned the Americans about the trap. On the 12th, Burgoyne and his officers agreed that they had no choice except to surrender, and on the 13th an officer came to Gates to request terms. Gates initially insisted on unconditional surrender, but soon reconsidered. Surrender terms were agreed on the 16th, and Burgoyne surrendered to Gates the following day.

Comparing Sobel with actual history, it seems as though the actual point of divergence must be Clinton setting out from New York City on schedule on September 22. Burgoyne continues to act as he did in our history, retreating north across the Fishkill River on October 9. Sobel doesn't mention the Battle of Bemis Heights, which might mean that it never took place. However, based on Burgoyne's retreat across the Fishkill, it seems likely that it did take place and Sobel simply chose not to mention it. By the time Burgoyne is offering to negotiate his surrender to Gates on October 13, as he did in our history, Clinton is closing in on Albany, and "smashes" an American army under Israel Putnam. Burgoyne by this time has received word of Clinton's approach, and instead of surrendering, he continues to sit tight. When Gates attacks on October 21, Burgoyne is able to drive him off, then attack in his turn the next day after Clinton attacks Gates from behind:

"Heartened by the sound of their comrades' bullets, Burgoyne's ragged force, now numbering less than 2,000, staged its final assault, in this way placing the now-panicky rebels in the jaws of a pincer movement. It was now Gates' turn to flee, and so he did. Within two days the rebels were on the outskirts of Albany, vulnerable to attack, unable to respond. On the afternoon of October 25, Burgoyne offered Gates a generous peace. All his troops could return to their homes, while Gates himself would be free to leave, upon his pledge never to fight again. The proposal was accepted; Gates had no choice but to do so. So ended one of the most glorious episodes in the history of eighteenth century warfare."

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Sobel Wiki: the king on a string

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is on France. As I've noted before, France suffers an even more unpleasant history in the Sobel Timeline than in our own, which may well reflect Sobel's annoyance at Charles de Gaulle's nationalist policies during the 1960s.

One of the minor puzzles of For Want of a Nail is trying to figure out the family relationships between the various French kings that Sobel mentions. We start off with the historical Louis XVI in the 1770s, but things become uncertain after Louis' accidental death in 1793. He is succeeded by his son Louis XVII, who is a minor at the time, and initially under a regency headed by his mother, Marie Antoinette. In our own history, all of Louis and Marie Antoinette's children were born after the October 1777 point of divergence, so the same children might not be born in the Sobel Timeline. However, all of the other royal families mentioned in Nail tracked closely with their counterparts from our world. Great Britain had a Queen Victoria and a Prince Albert in the 19th century, and Russia had a Tsar Nicholas II at the turn of the 20th century, so it seems reasonable to suppose that Louis and Marie Antoinette would have had the same four children they did in our history.

In our history, Louis's eldest son, Louis Joseph, died in infancy in June 1789 after a sudden illness, but it's anybody's guess whether the same would have happened in the Sobel Timeline. If it was Louis Joseph who succeeded to the throne, then he would have been just under twelve years old at the time of his accession. There is no further mention made of Marie Antoinette's regency after 1795, which suggests that Louis XVII reached his majority and ended his mother's regency during the course of the Trans-Oceanic War. Sobel's source for Louis XVII's reign after the end of the war is called The King on a String: The Last Years of Louis XVII, which suggests that Louis XVII did not make it very far into the 19th century.

The next French king to be mentioned is Louis XVIII, whose dislike of the British was shared by Mexican President Andrew Jackson in the 1820s. It is possible that Louis XVIII was a son of Louis XVII, but it is also possible that he was Louis Joseph's historical younger brother, Louis-Charles, born in 1785. It's even possible that he is our history's Louis XVIII, the younger brother of Louis XVI. Louis XVIII's Anglophobia suggests that he was an adult at the time of the Anglo-German occupation of Paris in the early 1800s, and thus was not the son of Louis XVII. All things considered, he was most likely the historical Louis-Charles.

The next French king is Henry V, who in 1845 was unable to provide aid to the Mexicans during the Rocky Mountain War due to France's "difficulties" with the Germanic Confederation. After him is Louis XIX, who looked upon the United States of Mexico as his protege and was willing to offer the Mexican government long-term loans in the late 1850s. Next is Louis XX, an older man who abdicated in early December 1879, and his son Louis XXI, who ruled for three weeks before being killed along with his siblings and parents by the Paris mob. Finally, there was the pretender Charles X, who sparked a civil war by landing at Calais in 1895 and claiming the French throne.

For those of you following along at home, that's six kings between 1793 and 1879, five of them named Louis. Apart from Louis XVI and his son Louis XVII, and Louis XX and his son Louis XXI, no family relationships are mentioned. Henry V may be the son of Louis XVIII; if so, he was probably born between 1810 and 1820; and based on his name, he was almost certainly a younger son who survived an older brother named Louis who died in infancy. Louis XIX is almost certainly a cousin who succeeded a childless Henry; he was probably a grandson of our history's Charles X, and would have been born around the same time as his cousin Henry, or perhaps as much as ten years earlier. Louis XX was probably the son of Louis XIX, but he might have been his younger brother. The pretender Charles X was probably a nephew of Louis XX and a first cousin of Louis XXI.

One of the minor puzzles of For Want of a Nail is trying to figure out the family relationships between the various French kings that Sobel mentions. We start off with the historical Louis XVI in the 1770s, but things become uncertain after Louis' accidental death in 1793. He is succeeded by his son Louis XVII, who is a minor at the time, and initially under a regency headed by his mother, Marie Antoinette. In our own history, all of Louis and Marie Antoinette's children were born after the October 1777 point of divergence, so the same children might not be born in the Sobel Timeline. However, all of the other royal families mentioned in Nail tracked closely with their counterparts from our world. Great Britain had a Queen Victoria and a Prince Albert in the 19th century, and Russia had a Tsar Nicholas II at the turn of the 20th century, so it seems reasonable to suppose that Louis and Marie Antoinette would have had the same four children they did in our history.

In our history, Louis's eldest son, Louis Joseph, died in infancy in June 1789 after a sudden illness, but it's anybody's guess whether the same would have happened in the Sobel Timeline. If it was Louis Joseph who succeeded to the throne, then he would have been just under twelve years old at the time of his accession. There is no further mention made of Marie Antoinette's regency after 1795, which suggests that Louis XVII reached his majority and ended his mother's regency during the course of the Trans-Oceanic War. Sobel's source for Louis XVII's reign after the end of the war is called The King on a String: The Last Years of Louis XVII, which suggests that Louis XVII did not make it very far into the 19th century.

The next French king to be mentioned is Louis XVIII, whose dislike of the British was shared by Mexican President Andrew Jackson in the 1820s. It is possible that Louis XVIII was a son of Louis XVII, but it is also possible that he was Louis Joseph's historical younger brother, Louis-Charles, born in 1785. It's even possible that he is our history's Louis XVIII, the younger brother of Louis XVI. Louis XVIII's Anglophobia suggests that he was an adult at the time of the Anglo-German occupation of Paris in the early 1800s, and thus was not the son of Louis XVII. All things considered, he was most likely the historical Louis-Charles.

The next French king is Henry V, who in 1845 was unable to provide aid to the Mexicans during the Rocky Mountain War due to France's "difficulties" with the Germanic Confederation. After him is Louis XIX, who looked upon the United States of Mexico as his protege and was willing to offer the Mexican government long-term loans in the late 1850s. Next is Louis XX, an older man who abdicated in early December 1879, and his son Louis XXI, who ruled for three weeks before being killed along with his siblings and parents by the Paris mob. Finally, there was the pretender Charles X, who sparked a civil war by landing at Calais in 1895 and claiming the French throne.

For those of you following along at home, that's six kings between 1793 and 1879, five of them named Louis. Apart from Louis XVI and his son Louis XVII, and Louis XX and his son Louis XXI, no family relationships are mentioned. Henry V may be the son of Louis XVIII; if so, he was probably born between 1810 and 1820; and based on his name, he was almost certainly a younger son who survived an older brother named Louis who died in infancy. Louis XIX is almost certainly a cousin who succeeded a childless Henry; he was probably a grandson of our history's Charles X, and would have been born around the same time as his cousin Henry, or perhaps as much as ten years earlier. Louis XX was probably the son of Louis XIX, but he might have been his younger brother. The pretender Charles X was probably a nephew of Louis XX and a first cousin of Louis XXI.

Thursday, May 2, 2013

The gift that keeps on giving

Tragedy struck a Kentucky home after a father gave his five-year-old son a pack of matches and a bucket of oily rags for his birthday...

Sunday, April 28, 2013

Sobel Wiki: last in the hearts of his countrymen

I'm back from my enforced hiatus in the land of inner-ear malfunctions with a new featured article at the Sobel Wiki on George Washington.

One of the original reviews of For Want of a Nail when it was first published forty years ago was called "If Washington Hadn't Been The Father of His Country", and alt-Sobel's treatment of the rebel general in the opening chapters helped set the book's tone. He spares no pains in giving the reader a negative portrait of Washington, writing, "A man of little talent and less imagination, though of great pride, Washington saw in the Rebellion a chance to make a career for himself, and so deserted his class for the sake of his ambition. Needless to say, his selection was the greatest mistake the rebels could have made."

This is the real Sobel showing us that alt-Sobel isn't entirely reliable as a narrator of his world's history. In fact, Washington's generalship in the period before Nail's point-of-divergence in October 1777 gained him considerable respect among Europeans who followed the American rebellion. Frederick the Great of Prussia spoke of Washington's victories at Trenton and Princeton thus: "The achievements of Washington and his little band of compatriots between the 25th of December and the 4th of January, a space of ten days, were the most brilliant of any recorded in the annals of military achievements." Washington's attack at Germantown, although unsuccessful, prompted the French foreign minister, the Count de Vergennes, to write, "Nothing has struck me so much as Gen. Washington's attacking and giving battle to Gen. Howe's army. To bring troops, raised within the year, to do this, promises everything."

The real Sobel highlighted alt-Sobel's bias by having his Mexican critic, Frank Dana, write, "The most serious problem is his presentation of the North American Rebellion, in which the loyalists could do no wrong, while the rebels are presented as fools, clowns, traitors, and knaves." The portrait alt-Sobel's draws of George Washington is probably Nail's clearest example of this.

The point, of course, is to let Sobel's readers know that this is not the American history they has been trained to expect. This is a loyalist perspective on the American Revolution from a world where the loyalist perspective is the priveleged one. In its way, Sobel's retelling of the American Revolution is a lesson on the unperceived biases that color our view of history.

One of the original reviews of For Want of a Nail when it was first published forty years ago was called "If Washington Hadn't Been The Father of His Country", and alt-Sobel's treatment of the rebel general in the opening chapters helped set the book's tone. He spares no pains in giving the reader a negative portrait of Washington, writing, "A man of little talent and less imagination, though of great pride, Washington saw in the Rebellion a chance to make a career for himself, and so deserted his class for the sake of his ambition. Needless to say, his selection was the greatest mistake the rebels could have made."

This is the real Sobel showing us that alt-Sobel isn't entirely reliable as a narrator of his world's history. In fact, Washington's generalship in the period before Nail's point-of-divergence in October 1777 gained him considerable respect among Europeans who followed the American rebellion. Frederick the Great of Prussia spoke of Washington's victories at Trenton and Princeton thus: "The achievements of Washington and his little band of compatriots between the 25th of December and the 4th of January, a space of ten days, were the most brilliant of any recorded in the annals of military achievements." Washington's attack at Germantown, although unsuccessful, prompted the French foreign minister, the Count de Vergennes, to write, "Nothing has struck me so much as Gen. Washington's attacking and giving battle to Gen. Howe's army. To bring troops, raised within the year, to do this, promises everything."

The real Sobel highlighted alt-Sobel's bias by having his Mexican critic, Frank Dana, write, "The most serious problem is his presentation of the North American Rebellion, in which the loyalists could do no wrong, while the rebels are presented as fools, clowns, traitors, and knaves." The portrait alt-Sobel's draws of George Washington is probably Nail's clearest example of this.

The point, of course, is to let Sobel's readers know that this is not the American history they has been trained to expect. This is a loyalist perspective on the American Revolution from a world where the loyalist perspective is the priveleged one. In its way, Sobel's retelling of the American Revolution is a lesson on the unperceived biases that color our view of history.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Vertigo

I recently suffered an attack of vertigo that has made it difficult for me to use a computer, so my appearances online will be few and far between. I'll be back if and when I recover.

Sunday, April 14, 2013

Sobel Wiki: Don't mourn, organize!

The major articles in the Sobel Wiki can be roughly divided into two categories, which might be called longitudinal and latitudinal. Latitudinal articles are generally about people or events, such as Ezra Gallivan or the Rocky Mountain War, and go into great detail (preferably as much detail as Sobel provides) on a limited period of time. Longitudinal articles are generally about places or organizations, such as Manitoba or the National Financial Administration, that are woven through For Want of a Nail like threads through a tapestry. This week's featured article is a longitudinal one on the labor union.

As I note in the article, all of the labor unions that Sobel mentions by name arise in the Confederation of North America. Partly this is due to the fact that the C.N.A. industrializes earlier, and to a much greater extent, than the United States of Mexico. Partly it is also due to the fact that Kramer Associates' control of the political system in the U.S.M. after 1869 would have ensured that no labor unions would develop there (Sobel specifically states that by the 1890s Mexico had no labor unions). Alt-Sobel, who tends to both glorify and whitewash K.A., never specifically connects K.A.'s political and economic power to the absence of unions in the U.S.M., but it isn't hard to imagine Bernard Kramer and Diego Cortez y Catalán engaging in union-busting, the former with his characteristic ruthlessness, the latter relying on Benito Hermión's Constabulary agents.

In the C.N.A., Sobel mentions textile workers organizing a union in Massachusetts in 1826, and the mill owners quickly crushing it. The first union to be mentioned by name is the Grand Consolidated Union, an early one-big-union established in 1835 and ruthlessly crushed by Henry Gilpin in the winter of 1840-41. Sobel then mentions three more unions being established after the Rocky Mountain War and gaining considerable political influence. A union official is elected to the Grand Council in 1893 and becomes the leader of the radical wing of the People's Coalition. An organization called the Workers' Army forms part of the League for Brotherhood in the early 1920s.

And that's it. Apart from that one brief reference to the Workers' Army, all of Sobel's labor history is confined to the 19th century. A comparable history of the USA would mention the United Autoworkers sit-down strike against G.M. in 1937, the A.F.L.'s split with the C.I.O. in 1938, and the merger of the two in 1955. Of course, both Sobel and alt-Sobel were business historians, and Nail reflects that, with much more space being given over to business history and the N.F.A. than to labor history.

As I note in the article, all of the labor unions that Sobel mentions by name arise in the Confederation of North America. Partly this is due to the fact that the C.N.A. industrializes earlier, and to a much greater extent, than the United States of Mexico. Partly it is also due to the fact that Kramer Associates' control of the political system in the U.S.M. after 1869 would have ensured that no labor unions would develop there (Sobel specifically states that by the 1890s Mexico had no labor unions). Alt-Sobel, who tends to both glorify and whitewash K.A., never specifically connects K.A.'s political and economic power to the absence of unions in the U.S.M., but it isn't hard to imagine Bernard Kramer and Diego Cortez y Catalán engaging in union-busting, the former with his characteristic ruthlessness, the latter relying on Benito Hermión's Constabulary agents.

In the C.N.A., Sobel mentions textile workers organizing a union in Massachusetts in 1826, and the mill owners quickly crushing it. The first union to be mentioned by name is the Grand Consolidated Union, an early one-big-union established in 1835 and ruthlessly crushed by Henry Gilpin in the winter of 1840-41. Sobel then mentions three more unions being established after the Rocky Mountain War and gaining considerable political influence. A union official is elected to the Grand Council in 1893 and becomes the leader of the radical wing of the People's Coalition. An organization called the Workers' Army forms part of the League for Brotherhood in the early 1920s.

And that's it. Apart from that one brief reference to the Workers' Army, all of Sobel's labor history is confined to the 19th century. A comparable history of the USA would mention the United Autoworkers sit-down strike against G.M. in 1937, the A.F.L.'s split with the C.I.O. in 1938, and the merger of the two in 1955. Of course, both Sobel and alt-Sobel were business historians, and Nail reflects that, with much more space being given over to business history and the N.F.A. than to labor history.

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Sobel Wiki: power to the people

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is on the People's Coalition, a populist political party in the C.N.A. that managed to do what our own history's Populists didn't: gain power. The People's Coalition is created in 1869 out of disparate groups of discontented people who are alienated from the existing political system by the corruption of the two major parties. The Coalition receives a major boost when the C.N.A.'s economy suffers a recession in the early 1880s. This enables Ezra Gallivan, the estranged son of a railroad tycoon, to win election as Mayor of Michigan City (our own world's Chicago). Gallivan proves to have a gift for political organization, and under his leadership the Coalition gains a plurality of seats in the Grand Council nineteen years after its founding.

Robert Sobel, the Australian business historian who is the nominal author of For Want of a Nail, is careful to avoid noting the strong ties between the founders of the Coalition and the leaders of the North American Rebellion of a hundred years earlier. The reason is clear enough: Sobel is utterly contemptuous of the rebels of '75, which he readily admits to at one point in the book, and which Professor Frank Dana of the United States of Mexico emphasizes in his critique of Nail. The last thing Sobel wants to do is admit that the Coalition, which has become thoroughly respectable at the time he is writing, drew its inspiration from the despised rebels.

Thus, Sobel mentions without comment the fact that the Coalition's founding document was called the Norfolk Resolves. He ignores the obvious implication of the Coalition winning control of the most pro-Rebellion areas of the C.N.A., the provinces of New Hampshire, Virginia, and North Carolina. He lays no stress upon the fact that Gallivan thoroughly distances the C.N.A. from Great Britain, in sharp contrast to his predecessor John McDowell's attempts to bring the two closer together.

Eventually, the People's Coalition falls victim to its own success. After thirty-five years of uninterrupted power, the Coalition becomes complacent. When a new protest movement appears in the early 1920s, its target is the same mechanized, industrialized, modern society that the Coalition had helped to create. Calvin Wagner, the fifth successive Coalitionist head of the C.N.A., is baffled by the challenge. Wagner becomes the first Governor-General to lose a re-election campaign since John McDowell, the man Ezra Gallivan defeated in 1888.

Robert Sobel, the Australian business historian who is the nominal author of For Want of a Nail, is careful to avoid noting the strong ties between the founders of the Coalition and the leaders of the North American Rebellion of a hundred years earlier. The reason is clear enough: Sobel is utterly contemptuous of the rebels of '75, which he readily admits to at one point in the book, and which Professor Frank Dana of the United States of Mexico emphasizes in his critique of Nail. The last thing Sobel wants to do is admit that the Coalition, which has become thoroughly respectable at the time he is writing, drew its inspiration from the despised rebels.

Thus, Sobel mentions without comment the fact that the Coalition's founding document was called the Norfolk Resolves. He ignores the obvious implication of the Coalition winning control of the most pro-Rebellion areas of the C.N.A., the provinces of New Hampshire, Virginia, and North Carolina. He lays no stress upon the fact that Gallivan thoroughly distances the C.N.A. from Great Britain, in sharp contrast to his predecessor John McDowell's attempts to bring the two closer together.

Eventually, the People's Coalition falls victim to its own success. After thirty-five years of uninterrupted power, the Coalition becomes complacent. When a new protest movement appears in the early 1920s, its target is the same mechanized, industrialized, modern society that the Coalition had helped to create. Calvin Wagner, the fifth successive Coalitionist head of the C.N.A., is baffled by the challenge. Wagner becomes the first Governor-General to lose a re-election campaign since John McDowell, the man Ezra Gallivan defeated in 1888.

The new Iraq

The Obama administration has officially released a budget plan that calls for cutting Social Security benefits, making him the first Democratic president to put Social Security cuts "on the table" as they say. Why? There are no good reasons, only several bad ones.

I think cutting Social Security is Barack Obama's version of invading Iraq. That is to say, it's a very harmful, very stupid, very unpopular policy that he has nevertheless been determined to pursue, by whatever means necessary, since the day he entered office.

I think cutting Social Security is Barack Obama's version of invading Iraq. That is to say, it's a very harmful, very stupid, very unpopular policy that he has nevertheless been determined to pursue, by whatever means necessary, since the day he entered office.

Monday, April 8, 2013

The wages of sanctity

Roy Edroso's latest column in the Village Voice is about conservatives' sudden desire to scold straight people for not getting married. A factoid that most of the wingnuts mention is that married people tend to be wealthier than single people. Needless to say, they know as well as you and I do that the chain of cause-to-effect there runs from money to marriage. Nevertheless, all the wingnuts pretend to believe that it's the other way around, that getting married causes people to become wealthier.

It isn't hard to see why they prefer to lie about the cause and effect. Given their insistence that marriage is a Good Thing, then if they admitted that financial security encourages marriage, they would have to embrace the idea that the way to get more people to marry would not be scolding them, but bribing them.

Since the wingnuts won't go there, I will. I hereby declare that marriage is a Good Thing, and that the government ought to encourage marriage by offering married couples a guaranteed annual income of $50,000. And since wingnuts are so insistent that the point of marriage is procreation, I further propose that the guaranteed annual income be doubled if the couple has a child, and doubled again for each subsequent child. The salary continues for as long as the couple is married; if they get divorced, it not only ends, but each person has to pay an annual divorce tax. (However, if the marriage ends with one spouse surviving the other's death, the surviving spouse continues to receive the full income.) Furthermore, in order to encourage couples to remain married to their original spouses, a second marriage does not result in resumption of the guaranteed income. And just to hammer home the fact that Divorce Is Bad, a second marriage that ends in divorce results in a doubling of the divorce tax.

And since I believe in rewarding past good behavior as well as future good behavior, I propose that couples who are already married should get their income retroactive to the year they were married. For instance, since I just celebrated my 15th wedding anniversary last week, my wife and I ought to receive a lump-sum payment of $750,000. And my parents, who will be celebrating their 60th wedding anniversary next year, ought to be getting . . . well, actually, this is going to be complicated. They married in 1954, and had six children over the next ten years, so their lump-sum payment would be:

1954: $50,000

1955 - one child: $100,000

1956 - two children: $200,000

1957 - three children: $400,000

1958 - three children: $400,000

1959 - four children: $800,000

1960 - four children: $800,000

1961 - four children: $800,000

1962 - five children: $1.6 million

1963 - six children: $3.2 million

and an additional $3.2 million dollars for every year from 1964 to 2012, which works out to $161.95 million dollars total.

Wingnuts, if you want to encourage marriage, that's the way to do it. No need to thank me, I'm happy to help, but you can contact me by email to offer me my Heritage Foundation fellowship.

It isn't hard to see why they prefer to lie about the cause and effect. Given their insistence that marriage is a Good Thing, then if they admitted that financial security encourages marriage, they would have to embrace the idea that the way to get more people to marry would not be scolding them, but bribing them.

Since the wingnuts won't go there, I will. I hereby declare that marriage is a Good Thing, and that the government ought to encourage marriage by offering married couples a guaranteed annual income of $50,000. And since wingnuts are so insistent that the point of marriage is procreation, I further propose that the guaranteed annual income be doubled if the couple has a child, and doubled again for each subsequent child. The salary continues for as long as the couple is married; if they get divorced, it not only ends, but each person has to pay an annual divorce tax. (However, if the marriage ends with one spouse surviving the other's death, the surviving spouse continues to receive the full income.) Furthermore, in order to encourage couples to remain married to their original spouses, a second marriage does not result in resumption of the guaranteed income. And just to hammer home the fact that Divorce Is Bad, a second marriage that ends in divorce results in a doubling of the divorce tax.

And since I believe in rewarding past good behavior as well as future good behavior, I propose that couples who are already married should get their income retroactive to the year they were married. For instance, since I just celebrated my 15th wedding anniversary last week, my wife and I ought to receive a lump-sum payment of $750,000. And my parents, who will be celebrating their 60th wedding anniversary next year, ought to be getting . . . well, actually, this is going to be complicated. They married in 1954, and had six children over the next ten years, so their lump-sum payment would be:

1954: $50,000

1955 - one child: $100,000

1956 - two children: $200,000

1957 - three children: $400,000

1958 - three children: $400,000

1959 - four children: $800,000

1960 - four children: $800,000

1961 - four children: $800,000

1962 - five children: $1.6 million

1963 - six children: $3.2 million

and an additional $3.2 million dollars for every year from 1964 to 2012, which works out to $161.95 million dollars total.

Wingnuts, if you want to encourage marriage, that's the way to do it. No need to thank me, I'm happy to help, but you can contact me by email to offer me my Heritage Foundation fellowship.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

Sobel Wiki: release the hounds

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is Henry Gilpin, the second Governor-General of the C.N.A. and the architect of the Rocky Mountain War.

As I've noted before, Robert Sobel had a tendency to allow people from our own history to play roles in For Want of a Nail despite having been born decades after his history branched away from ours. Gilpin is a rather extreme example. His parents were born 3,000 miles apart, and only met because Gilpin's father was visiting Lancaster, England in the 1790s.

On the other hand, the prominent role Gilpin plays in the history of the C.N.A. makes Gilpin the obverse to people like James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln, major figures from our history who play minor roles in the Sobel Timeline. In our own history, Gilpin's most notable accomplishment was being named Attorney General under President Martin van Buren in 1840. In the Sobel Timeline, he serves as Governor of the Northern Confederation for three years, a leading delegate to the Concordia Convention of 1841 and the Burgoyne Conference of 1842, one of the founders of the Unified Liberal Party, Minister of War under Governor-General Winfield Scott from 1843 to 1849, and Governor-General himself from 1849 to 1853, after engineering Scott's fall.

Gilpin is also one of the major villains of the Sobel Timeline, though alt-Sobel goes to some lengths to whitewash his actions. Gilpin's rule of the Northern Confederation in the early 1840s is dictatorial, as he oversees the suppression of the N.C.'s leading labor union during a bloody purge that costs the lives of over 40,000 people. As Minister of War, he maneuvers the C.N.A. into a war with the United States of Mexico, and as Governor-General, he sacrifices the lives of over a hundred thousand North American troops in a disastrous campaign aimed at capturing San Francisco, a city of no strategic value.

Writing Nail in the summer of 1971, Sobel happened to name two of the North American generals involved in Gilpin's ill-fated campaign David Homer and FitzJohn Smithers. Thirty years later, when I became involved in the For All Nails project, I found the coincidence irresistable, and I ended up writing a series of Rocky Mountain War-era vignettes with a definite Simpsons flavor in which Gilpin was modeled on Mr. Burns.

As I've noted before, Robert Sobel had a tendency to allow people from our own history to play roles in For Want of a Nail despite having been born decades after his history branched away from ours. Gilpin is a rather extreme example. His parents were born 3,000 miles apart, and only met because Gilpin's father was visiting Lancaster, England in the 1790s.

On the other hand, the prominent role Gilpin plays in the history of the C.N.A. makes Gilpin the obverse to people like James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln, major figures from our history who play minor roles in the Sobel Timeline. In our own history, Gilpin's most notable accomplishment was being named Attorney General under President Martin van Buren in 1840. In the Sobel Timeline, he serves as Governor of the Northern Confederation for three years, a leading delegate to the Concordia Convention of 1841 and the Burgoyne Conference of 1842, one of the founders of the Unified Liberal Party, Minister of War under Governor-General Winfield Scott from 1843 to 1849, and Governor-General himself from 1849 to 1853, after engineering Scott's fall.

Gilpin is also one of the major villains of the Sobel Timeline, though alt-Sobel goes to some lengths to whitewash his actions. Gilpin's rule of the Northern Confederation in the early 1840s is dictatorial, as he oversees the suppression of the N.C.'s leading labor union during a bloody purge that costs the lives of over 40,000 people. As Minister of War, he maneuvers the C.N.A. into a war with the United States of Mexico, and as Governor-General, he sacrifices the lives of over a hundred thousand North American troops in a disastrous campaign aimed at capturing San Francisco, a city of no strategic value.

Writing Nail in the summer of 1971, Sobel happened to name two of the North American generals involved in Gilpin's ill-fated campaign David Homer and FitzJohn Smithers. Thirty years later, when I became involved in the For All Nails project, I found the coincidence irresistable, and I ended up writing a series of Rocky Mountain War-era vignettes with a definite Simpsons flavor in which Gilpin was modeled on Mr. Burns.

Saturday, March 30, 2013

Sobel Wiki: a word from our sponsor

This week's featured article on the Sobel Wiki is Owen Galloway, locomobile magnate, philanthropist, pacifist, and a direct descendant of noted Loyalist Joseph Galloway. This presents a problem, because none of Joseph Galloway's sons survived to adulthood. When the fighting broke out in 1775, his only surviving child was his daughter Elizabeth. In our history, Galloway's wife Grace died in 1782, and we can only assume that she died around the same time in Sobel's history, and that Galloway remarried and had at least one son by his second wife.

In the Sobel Timeline, Owen Galloway played a similar role to that of our own history's Henry Ford, hitting on the idea of building low-cost cars for a mass market. He also dispayed a touch of William C. Durant by acquiring seven other locomobile companies and combining them into North American Motors, the world's largest car company. He then started up a subsidiary oil company to provide fuel for his cars, a subsidiary financial company to offer loans to car buyers, and a subsidiary motel chain to give motorists a place to stay the night.

Galloway's most significant accomplishment, though, had nothing to do with his car company. At a time when society in the C.N.A. was undergoing a major social disturbance, Galloway hit upon the idea of forming a trust fund to subsidize emigration by North Americans. This made Galloway the most popular public figure in the C.N.A., and his weekly vitavision addresses attracted larger audiences than any of the entertainment programs (except possibly his own Galloway Playhouse). Galloway wasn't interested in a political career, but Sobel reports that a whole generation of North American politicians courted popularity by imitating Galloway's wooden delivery.

In the Sobel Timeline, Owen Galloway played a similar role to that of our own history's Henry Ford, hitting on the idea of building low-cost cars for a mass market. He also dispayed a touch of William C. Durant by acquiring seven other locomobile companies and combining them into North American Motors, the world's largest car company. He then started up a subsidiary oil company to provide fuel for his cars, a subsidiary financial company to offer loans to car buyers, and a subsidiary motel chain to give motorists a place to stay the night.

Galloway's most significant accomplishment, though, had nothing to do with his car company. At a time when society in the C.N.A. was undergoing a major social disturbance, Galloway hit upon the idea of forming a trust fund to subsidize emigration by North Americans. This made Galloway the most popular public figure in the C.N.A., and his weekly vitavision addresses attracted larger audiences than any of the entertainment programs (except possibly his own Galloway Playhouse). Galloway wasn't interested in a political career, but Sobel reports that a whole generation of North American politicians courted popularity by imitating Galloway's wooden delivery.

Monday, March 18, 2013

Sobel Wiki: unilateral assured destruction

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is on the War Without War -- the Sobel Timeline's version of the Cold War. But as is usually the case with the Sobel Timeline, the differences are more important than the similarities.

To start with, unlike our own history, there was no ideological component to Sobel's version of the Cold War. Instead of two rival superpowers with rival ideologies, the War Without War has no less than five major powers facing off against each other: the Confederation of North America, the United States of Mexico, the British Empire, the German Empire, and the global supercorporation Kramer Associates. The British and the C.N.A. are allies (or at least, they are when the C.N.A. isn't feeling isolationist), but otherwise it's pretty much a free-for-all. And the closest thing to an ideological rivalry is the U.S.M.'s populist dictatorship versus K.A.'s corporate meritocracy, with the other three powers all being liberal democracies.

Also, our world's Cold War started with a nuclear stalemate between the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. In the Sobel Timeline, nuclear weapons are only invented fifteen years into the War Without War. And the result isn't so much a stalemate as a form of global blackmail. The atomic bomb is first invented by Kramer Associates, and K.A. President Carl Salazar explicitly threatens to use it against any nation that attempts to re-start the Global War. Sobel is at some pains to paint Richard Mason, the leader of the C.N.A., as a fool. Yet Mason is the only world leader to take Salazar at his word. Instead of attempting to replicate K.A.'s nuclear weapons program, Mason is content to allow the corporation to maintain its nuclear monopoly, and allow the C.N.A. to shelter under the nuclear umbrella of Salazar's Pax Kramerica.

The picture we get of the War Without War is ambiguous, because the artist who draws it is an unreliable one. The alternate Sobel who is the nominal author of For Want of a Nail is not an impartial observer of his world. He is a native of Australia, a country that was dependent on huge subsidies from Kramer Associates to survive the Global War, and a country that Sobel himself admits is becoming an economic colony of K.A. At the end of Nail, we learn that Sobel has emigrated to K.A.'s Taiwanese fiefdom under the patronage of Stanley Tulin, Carl Salazar's court historian. Nail can be seen (and in some quarters, we learn, is seen) as a work of K.A. propaganda, praising Salazar and his predecessors, vilifying his Mexican enemies, and seeking to sway North American public opinion away from the pacifistic Peace and Justice Party and towards the bellicose People's Coalition.

To start with, unlike our own history, there was no ideological component to Sobel's version of the Cold War. Instead of two rival superpowers with rival ideologies, the War Without War has no less than five major powers facing off against each other: the Confederation of North America, the United States of Mexico, the British Empire, the German Empire, and the global supercorporation Kramer Associates. The British and the C.N.A. are allies (or at least, they are when the C.N.A. isn't feeling isolationist), but otherwise it's pretty much a free-for-all. And the closest thing to an ideological rivalry is the U.S.M.'s populist dictatorship versus K.A.'s corporate meritocracy, with the other three powers all being liberal democracies.

Also, our world's Cold War started with a nuclear stalemate between the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. In the Sobel Timeline, nuclear weapons are only invented fifteen years into the War Without War. And the result isn't so much a stalemate as a form of global blackmail. The atomic bomb is first invented by Kramer Associates, and K.A. President Carl Salazar explicitly threatens to use it against any nation that attempts to re-start the Global War. Sobel is at some pains to paint Richard Mason, the leader of the C.N.A., as a fool. Yet Mason is the only world leader to take Salazar at his word. Instead of attempting to replicate K.A.'s nuclear weapons program, Mason is content to allow the corporation to maintain its nuclear monopoly, and allow the C.N.A. to shelter under the nuclear umbrella of Salazar's Pax Kramerica.

The picture we get of the War Without War is ambiguous, because the artist who draws it is an unreliable one. The alternate Sobel who is the nominal author of For Want of a Nail is not an impartial observer of his world. He is a native of Australia, a country that was dependent on huge subsidies from Kramer Associates to survive the Global War, and a country that Sobel himself admits is becoming an economic colony of K.A. At the end of Nail, we learn that Sobel has emigrated to K.A.'s Taiwanese fiefdom under the patronage of Stanley Tulin, Carl Salazar's court historian. Nail can be seen (and in some quarters, we learn, is seen) as a work of K.A. propaganda, praising Salazar and his predecessors, vilifying his Mexican enemies, and seeking to sway North American public opinion away from the pacifistic Peace and Justice Party and towards the bellicose People's Coalition.

Friday, March 8, 2013

Sobel Wiki: the border that wasn't

This week's featured article on the Sobel Wiki is the Confederation of Southern Vandalia, Sobel's "black confederation" (the scare quotes are his). As I've noted before, Southern Vandalia was part of Sobel's alternate version of American race relations, a part of the C.N.A. where black North Americans could, to use a modern expression, escape the kyriarchy that dominated the rest of the country, and establish a society that was, if not color-blind, then at least biased in the other direction. Sobel's majority-black confederation was established in 1877. By the turn of the 20th century, young black Southern Vandalians who were the product of that society began emigrating to the majority-white areas of the C.N.A., seeking opportunities that weren't available in their own decidedly rural home state. By the middle of the century, racial animosity in the C.N.A. had receded to the point where there were, to use another modern expression, no racial dog-whistles employed when black and white candidates campaigned against each other for the office of chief executive.

For students of Sobel's alternate history, however, Southern Vandalia is as much a cartographical puzzle as a sociological one. On page 140, Sobel has this to say on the separation of Vandalia into northern and southern sections:

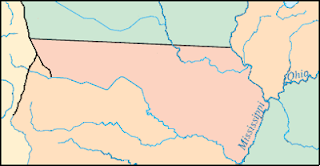

But if you look at the frontispiece map in Nail, you'll find that it shows Southern Vandalia looking like this:

So, how do you reconcile the contradiction between the text and the only actual map of the C.N.A. that we have access to?

The standard solution is to ignore the map and stick to the 40th parallel as the boundary between Northern and Southern Vandalia. But I admit that I'm becoming less satisfied with that answer than I used to be. Those of us who have spent far too much time studying the Sobel Timeline have explained away much knottier contradictions than this.

In this case, I think the thing to bear in mind is that not all geographical expressions are meant to be taken literally. In our own history, for example, "the Mason-Dixon line" is used as shorthand for "the boundary between free states and slave states/former slave states" even though the actual Mason-Dixon line was simply the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania. In the same way, it's possible that in the Sobel Timeline, "the 40th parallel" was used as shorthand for the boundary between majority-white and majority-black areas of Vandalia. When it came time to draw the actual boundary, though, the Grand Council did some gerrymandering to ensure that as many of Vandalia's black residents were south of the line, and as many whites were north of it, as possible.

Of course, if we accept this interpretation of "the 40th parallel", it will mean redrawing most of the maps on the Sobel Wiki. But since they'll conform more closely with the source material, it would be a change worth making.

I solicit the opinions of other Sobel scholars on the question.

For students of Sobel's alternate history, however, Southern Vandalia is as much a cartographical puzzle as a sociological one. On page 140, Sobel has this to say on the separation of Vandalia into northern and southern sections:

This fast growth created problems of administration, and in addition, there were conflicts between miners and farmers, immigrants and native-born Americans, settlers from Indiana and the N.C. on the one side and the S.C. on the other. Because of this, all members of the Grand Council but four recommended the division of the confederation. Governor Hiram Potter also supported division, which was accomplished in 1877. Northern Vandalia (the area north of the 40th parallel) contained the mines, many foreign-born and Indiana-N.C. settlers, and wheatlands, while Southern Vandalia had almost all the S.C. immigrants, the richest farmlands in the region, and the largest proportion of Negro North Americans in the C.N.A.So, based on Sobel's reference to the 40th parallel, a typical map of Southern Vandalia looks like this:

But if you look at the frontispiece map in Nail, you'll find that it shows Southern Vandalia looking like this:

So, how do you reconcile the contradiction between the text and the only actual map of the C.N.A. that we have access to?

The standard solution is to ignore the map and stick to the 40th parallel as the boundary between Northern and Southern Vandalia. But I admit that I'm becoming less satisfied with that answer than I used to be. Those of us who have spent far too much time studying the Sobel Timeline have explained away much knottier contradictions than this.

In this case, I think the thing to bear in mind is that not all geographical expressions are meant to be taken literally. In our own history, for example, "the Mason-Dixon line" is used as shorthand for "the boundary between free states and slave states/former slave states" even though the actual Mason-Dixon line was simply the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania. In the same way, it's possible that in the Sobel Timeline, "the 40th parallel" was used as shorthand for the boundary between majority-white and majority-black areas of Vandalia. When it came time to draw the actual boundary, though, the Grand Council did some gerrymandering to ensure that as many of Vandalia's black residents were south of the line, and as many whites were north of it, as possible.

Of course, if we accept this interpretation of "the 40th parallel", it will mean redrawing most of the maps on the Sobel Wiki. But since they'll conform more closely with the source material, it would be a change worth making.

I solicit the opinions of other Sobel scholars on the question.

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Sobel Wiki: a post-racial society

This week's featured article at the Sobel Wiki is on James Billington, the first black governor-general of the C.N.A. Sobel wrote For Want of a Nail in the summer of 1971, a time when race relations in the United States were at a low point. Every summer since the mid-1960s, there had been riots in the black ghettos of major American cities. In a way, this was actually a positive development, because it meant that African-Americans were actually fighting back against the institutionalized racism that had always been a feature of American society. At the time, though, it must have looked like the country was about to descend into an all-out racial civil war.

Ten years earlier, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy had said that "There's no question that in the next thirty or forty years, a Negro can also achieve the same position that my brother has as President of the United States, certainly within that period of time." By 1971, though, it was an open question whether there would be any black people in the United States, or even whether there would be a United States, by 2001, much less a black president.

Obviously, America had taken a wrong turning somewhere, so Sobel decided to map out a more racially harmonious alternative. In the C.N.A., abolitionists take advantage of a slump in the price of slaves in the late 1830s to pass a generous compensated manumission bill (as opposed to our own history's executive order during a civil war in 1862). And Sobel never comes right out and says so, but the lack of violent opposition is almost certainly due to the presence of an escape hatch for slavery supporters: any slaveowner who doesn't want to see his slaves freed can, and presumably does, pack up and move across the Mississippi to Jefferson. (John Calhoun is the same staunch defender of slavery in the Sobel Timeline that he is in our own. Sobel never mentions Calhoun's reaction to the passage of the Lloyd Manumission Bill in 1840. He does mention a freed slave in 20th century Mexico named Miguel Calhoun, and allows the reader to draw his own conclusions.)

The next component of Sobel's racial utopia is Southern Vandalia, basically our own history's Kansas and Missouri, an area of the C.N.A. which attracts about half of the freed slaves and their children in the 1860s and 1870s, to the point where blacks make up a majority of its population. In fact, Southern Vandalia serves as a refuge for the U.S.M.'s black population as well, since Sobel explicitly says that most of the slaves born there after 1855 escaped across the border to the C.N.A.

Not that every freed slave went to Southern Vandalia to participate in this self-imposed apartheid. Sobel records that of the C.N.A.'s black population of 5.9 million in 1880, a million lived in the Northern Confederation, another 1.1 million lived in the Southern Confederation, and another 1.6 million lived in the confederations of Quebec, Indiana, Northern Vandalia, and Manitoba.

And all was not sweetness and light. When the governor of Southern Vandalia founded an organization called the Friends of Black Mexico to agitate for the abolition of slavery there, his supporters were subject to violent attacks by white racists everywhere but Manitoba. The solution to lingering white racism turned out to be a wave of emigration by blacks and whites in the 1920s, subsidized by the C.N.A.'s version of Henry Ford.

By 1938, the People's Coalition was able to win a narrow governing majority in the Grand Council by pledging to support a black candidate for Council President, an office that was a sort of combination Speaker of the House and Vice President. Twelve years later, this Council President, James Billington, succeeded to the governor-generalship himself.

Billington is much like our own history's Barack Obama, a political moderate who makes of point of drawing as little attention to his race as possible. The major contrast between Sobel's history and our own is in their opponents. Sobel records that Billington's opponents attack him for his policies rather than his race. He is defeated in the 1953 elections by Richard Mason, a more liberal candidate whose own campaign is based on an appeal to guilt rather than racism.