For students of Sobel's alternate history, however, Southern Vandalia is as much a cartographical puzzle as a sociological one. On page 140, Sobel has this to say on the separation of Vandalia into northern and southern sections:

This fast growth created problems of administration, and in addition, there were conflicts between miners and farmers, immigrants and native-born Americans, settlers from Indiana and the N.C. on the one side and the S.C. on the other. Because of this, all members of the Grand Council but four recommended the division of the confederation. Governor Hiram Potter also supported division, which was accomplished in 1877. Northern Vandalia (the area north of the 40th parallel) contained the mines, many foreign-born and Indiana-N.C. settlers, and wheatlands, while Southern Vandalia had almost all the S.C. immigrants, the richest farmlands in the region, and the largest proportion of Negro North Americans in the C.N.A.So, based on Sobel's reference to the 40th parallel, a typical map of Southern Vandalia looks like this:

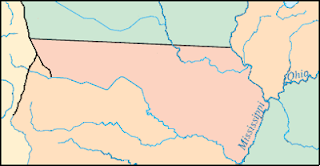

But if you look at the frontispiece map in Nail, you'll find that it shows Southern Vandalia looking like this:

So, how do you reconcile the contradiction between the text and the only actual map of the C.N.A. that we have access to?

The standard solution is to ignore the map and stick to the 40th parallel as the boundary between Northern and Southern Vandalia. But I admit that I'm becoming less satisfied with that answer than I used to be. Those of us who have spent far too much time studying the Sobel Timeline have explained away much knottier contradictions than this.

In this case, I think the thing to bear in mind is that not all geographical expressions are meant to be taken literally. In our own history, for example, "the Mason-Dixon line" is used as shorthand for "the boundary between free states and slave states/former slave states" even though the actual Mason-Dixon line was simply the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania. In the same way, it's possible that in the Sobel Timeline, "the 40th parallel" was used as shorthand for the boundary between majority-white and majority-black areas of Vandalia. When it came time to draw the actual boundary, though, the Grand Council did some gerrymandering to ensure that as many of Vandalia's black residents were south of the line, and as many whites were north of it, as possible.

Of course, if we accept this interpretation of "the 40th parallel", it will mean redrawing most of the maps on the Sobel Wiki. But since they'll conform more closely with the source material, it would be a change worth making.

I solicit the opinions of other Sobel scholars on the question.

2 comments:

I was one of the leading voices in For All Nails for viewing the frontspiece map as non-canon. There was the Maryland-Delaware business (where the text is itself contradictory) and the borders of Nova Scotia, not to mention Noel's expert opinion about the Mexican borders.

(To be fair, the borders of Nova Scotia on the map make more sense to me now than they did to me then, but I still don't buy the transfer of uninhabited IOW New Brunswick from loyal Quebec to the treasonous New England provinces of the NC.)

With regard to SV, you have at least one good point. The divisions of the IOW USA along lines of latitude or longitude occurred largely when the areas in question were relatively uninhabited by white or black people. But SV was pretty heavily settled before the division, and Sobel explicitly says that dividing the races was a goal of the division. You wouldn't think that they would just draw the 40-degree line on the map through existing farms and towns. On the other hand, I could easily see the 40-degree line being created as an administrative division when Vandalia was first created, and then being the most convenient place for a split later.

We should also look at the geography of the frontspiece map. By your theory, there was heavy black settlement of IOW Iowa before the split. Given the record of North American racial fairness in both timelines, I would have expected the blacks to wind up disproportionately in the poorer farmland, like say western Kansas rather than Iowa, with the latter being grabbed up by more prosperous whites before the wave of black immigration. But maybe not -- IOW Iowa had only 40,000 people in 1840, 200,000 in 1850, and 675,000 in 1860, so the wave came after liberation in the CNA. Ceteris paribus, of course.

As far as the Northern Confederation goes, I think we can chalk that up to cartography rather than history. The prewar borders are there, they're just hidden under the words NORTHERN CONFEDERATION.

As for the settlement of Vandalia by freed slaves, I think we can get this result by considering how the ex-slaves were released from their de facto state of serfdom. Sobel says that in 1860 more than half of the black population of the S.C. was still bound to the soil. I picture the quasi-serfdom ending first in Maryland and Virginia, then in North Carolina, and last of all in South Carolina and Georgia. The freedmen from IOW Kentucky who left there would have emigrated across the Ohio to Indiana, then in all likelihood would have been harrassed to the point of heading west across the Big Muddy to IOW Missouri and Iowa. Later freedmen from IOW Tennessee and Mississippi would have gone directly across the river to IOW Arkansas.

As for the idea of whites grabbing up all the best farmland, Sobel did explicitly say that SV had "the richest farmlands in the region", which agrees with the border from the frontispiece map.

Post a Comment